(1) PURPOSE OF THE DESIGN GUIDELINES

The City of Kent has a distinct character defined by the architecture of its environment. Preserving the character of the city is important to promote civic pride and economic vitality. Promoting awareness for future generations is a key to retaining the city's appeal and success. Recognizing the importance of the city's architectural history and aesthetic help complete the steps needed to keep the city's integrity intact. This recognition can be achieved through education, effort and imagination. These enduring attributes create an inviting place for visitors and residents as well as a pleasant working environment.

Kent's physical attributes are defined by its wonderful location on the Cuyahoga River, the Ohio and Erie Canal and the Atlantic and Great Western Railroad. These particularly charming assets of the city determined the social and economic history of Kent. The physical attributes of the defined area are collectively referred to as a cultural landscape. Cultural landscapes are developed over time and can be read and studied by the form and type of the buildings and landscapes that remain.

The City of Kent is known for taking advantage of the natural resources of the area and keeping up with the changing modes of transportation. The city was established because settlers saw the potential and the power of the Cuyahoga River, thus sparking the initial growth of the community. The canal and railroad followed soon thereafter, creating an economic growth and boom for the emerging city. These times of growth were influential to the city's planning and architecture and are still apparent in the physical form of the city.

These Design Guidelines provide assistance in maintaining or improving the present quality of life through preservation and rehabilitation of the city's architecture while accommodating new construction and modifications. This document provides tools, resources, and design guidance for application to numerous circumstances and settings. Illustrative examples and photographs are included to assist property owners with understanding specific situations. These Guidelines will be used in conjunction with one or more overlay districts designated by Kent City Council as outlined in Chapters Section 1111.04 of the Kent Zoning Code.

New construction near historic structures, or in an historic district, should complement and support the surrounding context in order to uphold the historic integrity of the city, be it traditional or contemporary stylistically.

The Guidelines are based upon the ideas and values set forth by the United States Secretary of the Interior's Standards for Rehabilitation. The Standards pertain to the repair or alteration of historic properties and have been this country's model for preservation practice for more than forty years.

(2) DEVELOPMENT OF THE DESIGN GUIDELINES

The City of Kent currently has three National Register Historic Districts and numerous properties listed in the National Register of Historic Places. Kent has a great collection of rich and diverse architecture that reflects the history of the city through the years. Kent's Design Overlay District gives the community an opportunity to protect the unique character of the area without having to rezone other districts.

The Kent Design Guidelines are intended to assist the community in preserving and enhancing places of special character. These guidelines are written to be utilized by property owners, tenants, building managers, property caretakers, architects, and builders that would be conducting work affecting an historic property. The Guidelines provide a framework for making good decisions about rehabilitation and new design. Recommendations, photographs and drawings offer information and advice on how to achieve appropriate design solutions for various types of properties within the overlay district(s) and also throughout the City of Kent.

The Guidelines present recommendations with the idea that it is better (also less expensive) to repair rather than to replace an original feature. However, these Guidelines are made to be flexible and serve as guidance for creative design solutions. The format of the guidelines begins with an historical overview of the City of Kent and then continues to discuss the different architectural styles that can be found in Kent. Design Principles for a building addition or constructing a new building adjacent to historic properties are also discussed within the design guidelines. Finally, the issues of site considerations, accessibility, graphics / signage, building color, and demolition can be found.

Historic preservation grows to be most successful when a community like Kent comes together with the same purpose in mind: to protect and reuse their historic resources.

The Certified Local Government, which is also a future option for Kent is sponsored by the Ohio Office of Historic Preservation program to encourage and acknowledge those communities with needed support, for processes like those described herein. Certified Local Governments, also known as CLG's, work as a federal-state-local partnership. The communities that become part of the CLG program benefit by receiving encouragement, education and funding through federal grants. The process of the Design Guidelines is meant to protect and enhance the overall value of the property while accommodating a contemporary use.

(3) DESIGN GUIDELINES GOALS

• Achieve good design to help economic vitality and sustain property values.

• Ensure that visual identity remains cohesive.

• Facilitate connectivity with Kent State University.

• Assist with the transition from an Architectural Advisory Board to an Architectural Review Board, which functions as one part of the City's overall development review process.

• Assist developers with design guidance; educate public about good design and incentives.

• Make Kent a destination place for visitors.

• Attempt to preserve, when possible and practical significant structures.

(4) PROCESS

In order to bring about a document that can be supported by the public, it was essential that there be public involvement in the process. Sponsored by the City of Kent, the Burbick Foundation, and Main Street Kent, this project began with stakeholder participation, has been sustained by public input, and will culminate with a presentation to the City Council.

The committee responsible for following this project through to completion was comprised of building owners, design and planning professionals, real estate professionals, developers, Kent homeowners, a University representative, and other active members of the Kent community who met on a regular basis to review, critique, and react to recommendations. Because this committee was tireless in their efforts to review and improve the document, the Design Guidelines for the City of Kent is well-vetted.

In the initial stages, as history and documentation were gathered, stakeholders from many different corners of the Kent community gathered to share and learn about the process of developing and implementing design guidelines. At two separate stakeholders meetings, business owners, homeowners, landowners, designers, representatives from the City and Kent State University joined developers, attorneys, members of Main Street Kent and the Kent Historical Society to discuss their ideal visions for the city. Even more exhilarating was the pride and passion with which each person described the current attributes of the Tree City.

From these conversations, several goals were established. (Goals are listed in Appendix A(3) in the "Development" section of these guidelines.) In order to invite input from another group of community members, these same goals were presented at a large and open public meeting held at the Kent Stage. At the end of the meeting, the participants were invited to prioritize the goals passed on to them by the stakeholders groups.

Overwhelmingly, the top goal selected was:

"Perpetuate good design to help economic vitality and to sustain property values."

The second goal selected was:

"The City can remain cohesive in visual identity."

The two goals ranking third are:

"Better connection with the University" and

"Transition from Architectural Advisory Board to Architectural Review Board."

Ranking these few goals ahead of the others does not diminish their significance entirely. The remaining goals may be lofty but also may be achieved by working toward the above priorities.

"Assist developer with guide to design."

"Education. General Public should become aware of value of good design and the incentives to reach it."

"Can we make Kent a fun place to be? A destination point for visitors."

"Save significant structures, demolitions should be reviewed, as should what takes its place."

"Define the boundaries of a district, but guidelines should help all of Kent."

With the information gained from the stakeholder and public meetings, the consultants assembled this set of Design Guidelines. The first and second draft copies were reviewed by the original committee. The presentation of the final draft was given at the April 22, 2009 City Council meeting. On November 18, 2009, Kent City Council adopted the Guidelines for the purpose of using the Guidelines in relation to projects which are receiving some form of City funding or financial assistance. The present effort would adopt the Guidelines as an overlay district in one or more areas of the City along with specific criteria and procedures for their implementation.

This process meets the criteria for the Certified Local Government application requirements.

(5) BENEFITS TO A PROPERTY OWNER

Good design and well-executed design guidelines have proven to be beneficial to both the property owner and the community because they sustain social and economic growth. Individual property values are enhanced through good design, and collectively, these properties can greatly increase the appearance of an entire district. The area becomes a destination that people want to visit and gives the city an identity. A place is created where the community interacts, thereby strengthening the ties between its members and the surrounding area. Activity supports local businesses including restaurants, retail, and entertainment establishments. The return on the investment in time and expense is to achieve good design in preservation, restoration, renovation, and new construction, a prolonged value that far exceeds the initial investment.

Economic benefits (besides the obvious increase in pedestrian traffic) can include use of preservation grants and loans, rehabilitation tax credits, energy efficiency tax breaks, and participation in Certified Local Government grants and loans. Design guidelines not only provide an opportunity to increase property value and appearance but become a tool in protecting the value of public and private investments. Areas that may be threatened by poorly- managed growth now have the opportunity to be managed by the community. There is also the benefit of attracting good developers to a thriving well-maintained community. The Guidelines are a means to assist clients and their designers in preliminary design or maintenance work; they will help keep the character of the town intact and the community thriving.

(6) FOR MORE INFORMATION ON THESE AND OTHER PROGRAMS TRY THE FOLLOWING WEBSITES:

• National Park Service, www.nps.gov

• Ohio Preservation Office, www.ohiohistory.org/resource/histpres

• Main Street Kent, www.mainstreetkent.org

• City of Kent Community Development, www.kentohio.org/dep/comdev.asp

(7) THE HISTORY OF KENT

The native Iroquois tribe used the Cuyahoga River's resources and Standing Rock as a landmark. Early settlers of Kent were unquestionably attracted to the area because of the Cuyahoga River. The settlers were attracted to the land because of the water power of the Cuyahoga River. The river had enough force to operate numerous mills, distilleries, tanneries and forges.

Aaron Olmstead, a business man from Connecticut saw the potential of the land and bought the twenty-five (25) square mile township which he named after his son, Franklin. In 1805, the Haymaker family became one of the first to establish themselves on what is now known as Kent. Jacob Haymaker, a German millwright and carpenter, bought 8 township lots along the river and Haymaker sent his son John with his wife and three children to begin construction of a mill and dam. The Haymakers were followed by many other businessmen that saw the potential of the river.

Later, in 1810, a growth in population established the community that came to be known as Franklin Mills. The residents considered the area divided and referred to it as the "Upper Village" and "Lower Village."

In 1825, the "Upper Village" was recorded as the village of Carthage but the name did not stick; the residents preferred to use the name Franklin Mills. During the era of the stage coach many rivalries grew between the two villages; businesses began advertising wars to persuade visitors passing through to come to their business rather than the one in the rival village. During these years of growth, a sawmill was built in 1814, which allowed residents to build frame houses rather than log cabins.

[1 Grismer, Karl H., History of Kent (Record Publishing Co., 2001)17.]

In 1816, the Franklin Mills community constructed a small cabin for their first school, and in 1820, the first post office was established: George DePeyster became the first Postmaster. By 1835, Franklin Mills' population grew to 1,400 people and included gristmills, woolen mills, cabinet shops, glass shops and tanneries.

The development of the Pennsylvania and Ohio canal began in the Franklin Mills area during the 1830s and was completed by 1840. The construction of the canal brought a lot of business to Franklin Mills and was a fundamental part of the growth of the community. This area is now known as the business district. The canal was a great resource that connected Franklin Mills to Pennsylvania, Ohio, Lake Erie and Akron. The canal era ended due to the development of the railroad.

Train tracks were laid in Franklin Mills by 1863. In 1864 the trunk line was complete connecting the town to St. Louis and New York. Marvin Kent had a big part in getting the Atlantic and Great Western railroad routed through Franklin Mills. The railroads helped keep the mills in business and thriving. Due to the location of Franklin Mills, it became the chosen spot to build the railroad shops which offered several hundred men jobs in the area and turned Franklin Mills into a prosperous railroad center. The residents were so grateful to Marvin Kent for his part in bringing railroads to Franklin Mills that they changed the name of the village to Kent in his honor. The state of Ohio made the Village of Kent official in 1867 by acknowledging the new name and incorporated it. In 1875, a new railroad depot was opened in a large brick building currently housing the Pufferbelly Restaurant on what is now Franklin Avenue.

In the early 1900s, there was a shortage of nearly 5,000 teachers in the state of Ohio. A law was passed looking for two new locations for a Teachers College: one in the western half of Ohio and one in the eastern half of the state. Kent pushed to become home to one of the schools and formed the Kent Board of Trade, and began the slogan "Home of the Hump and Hustle". William S. Kent donated a large area of land to the community for the school.

In 1910 Kent's hard work paid off and the state of Ohio gave Kent the opportunity to house one of the new public teachers' colleges, Kent State Normal School, now known as Kent State University. The arrival of the college generated another boom in Kent. Real estate values around the college drastically increased and more streets were constructed in the area. Construction workers building the college brought business to the town which were later followed by faculty and students.

In the 20th century, Kent saw an industrial boom as businesses considered Kent an excellent site to manufacture goods. The Davey Tree Expert Company is one of the most well-known businesses that was established in Kent; founded in 1909 by John Davey. The Davey Tree Expert Company is a leader in their industry and by 1920 the company was given 14 patents. The company headquarters still remain in Kent, but have additional offices throughout the country and in Canada. The company developed techniques such as line clearance and vegetation management for utility companies and the removal of large trees. The company made significant advances in the technology of bucket trucks, insect control, brush chippers and speed saws.

John Davey's son, Martin L. Davey, is known at a state level for being elected governor of Ohio. Martin graduated from Kent's high school and later attended Oberlin College. Martin was elected mayor of Kent in 1915 and 1917. In 1918 he held a position in the House of Representatives as a Democrat. He was re-elected to the House three more times before running for governor in 1928. After losing his first race he won in 1934 and was re-elected two years later. Martin returned to the family business full-time after serving as the governor.

(8) ENVIRONMENTAL FEATURES

In addition to architectural style, the natural environments in which the buildings are set contribute to the character of the Kent Design Overlay District. The Cuyahoga River flows through the center of the City of Kent. The water source for the gristmills of the original village and later the Pennsylvania and Ohio Canal resulted in the establishment of a thriving industrial town, and the Cuyahoga River remains an important resource of natural beauty and recreation for the community today.

The monumental Kent Dam, hand cut from sandstone in the form of a sweeping arch and the only known dam of its kind attached to a canal lock, still stands as an historic tribute to Kent's industrial past. The dam, built in 1836, has been listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

For environmental reasons, the river has been rerouted through the historic canal lock and the area behind the dam is now home to the green lawn, gardens, and observation platforms of Heritage Park. The majestic waterfall cascading over the dam remains as a symbolic backdrop for the City of Kent.

There are also several wooded parks located along the river's edge. In addition to being sites of scenic beauty and rich ecosystems, these parks also offer a multitude of opportunities for outdoor activities: hiking trails, recreational facilities, observation decks and beach-like landing spots to encourage community participation in the natural environment. Adding to the greenery of the natural landscape, the ambitious effort of planting hundreds of trees around the city, undertaken by John Davey in 1880, resulted in the city of Kent being designated as the first "Tree City" in America. The tree, as a representation of the city of Kent, has earned a place of honor on the official city logo.

(9) ARCHITECTURAL STYLES

Styles refer to trends in design that were influenced by the popular culture of their time period. They reflect fashion, and political and social influences of the day. Typology refers to building form and traditional methods of building, typically handed down through generations, and vernacular styles of local craftsmen. Typology can also refer to the original use of the building, such as a church, school, barn, depot, mill or residence. Residences often exhibit a mixture of styles indicating a transition from one style to the next or later additions and renovations made to the structure in the fashion of that time.

The architectural style of a building is expressed through the structure's character, which is defined by the floor plan and three-dimensional shape of the structure, and expressed through its details including windows, doors, chimneys, porches, and ornament. Kent architecture is characterized by the styles listed on this page. Dates refer to the era of popularity in Kent and in Ohio.

Mid-19th Century

Greek Revival (1835-1860)

Gothic Revival (1840-1880)

Italianate (1850-1880)

Late 19th Century

Second Empire (1855-1885)

Eastlake (1880-1890)

Romanesque Revival (1880-1900)

Queen Anne (1880-1905)

Italian Renaissance (1890-1935)

Neoclassical (1895-1950)

Early 20th Century

Craftsman (1900-1925)

Tudor Revival (1910-1940)

(10) GREEK REVIVAL STYLE (1835-1860)

The Greek Revival style was the dominant style in the United States from about 1835 to 1860. During this time period Americans were looking for a style that represented the ideals of democracy. They wished to distinguish the relatively new country of the United States from England. Classical architecture from Rome and Greece became the popular models. Americans were also very sympathetic to the Greek War of Independence which began in the 1830s. The Greek Revival style proliferated through carpenter pattern books, such as those by Asher Benjamin, and became so popular that it was known as the National Style. The style is found in many forms, based on its geographical location and use (urban or rural/residence or commercial).

Greek Revival's roof and porch are emphasized with a classical entablature, which is made up of a cornice, frieze and architrave. The architrave is typically bold and composed of a post and lintel arrangement. The porches are supported by square or rounded columns, usually of the Doric type. The front paneled door is single or paired and surrounded by elaborate details typically with narrow sidelights with a decorative frame.

The example below was most likely a one and one-half (1-1/2) story Greek Revival structure with a lower slope roof. At some point the roof pitch was changed to increase the house to two (2) stories.

(11) IDENTIFYING FEATURES

Classical entablature

Transoms and/or sidelights

Double-hung windows

Classical details

Greek key ornament

Acanthus leaf ornament

Full-width or entry porches

Square or round columns

Gabled or Hipped Roof

(12) GOTHIC REVIVAL STYLE (1840-1880)

Gothic Revival style first appeared in the United States in the mid-19th century during the Romantic period, when Picturesque Architecture was gaining popularity. Many contemporary publications written at the time sparked popularity, such as A.J. Davis' Rural Residences, A.J. Downing's Cottage Residences and Richard Upjohn's Rural Architecture. These books included drawings, details and landscape plans as a "How To" book.

Gothic Revival structures are medieval in form and have a vertical emphasis found in stone, brick and wood-framed details. This style has steeply pitched roofs and steep cross gables with decorated vergeboards. Tall clustered chimney stacks occur frequently. The windows extend into the gables having pointed arches with a drip-mold above the windows. The doors are decorated very similarly to the windows with pointed arches or other Gothic motifs and a decorative crown. The majority of the porches are one story with a flattened Gothic arch.

(13) IDENTIFYING FEATURES

Steeply Pitched Roofs

Pointed Arches

Vergeboards

Symmetrical

Medieval Form

Vertical Emphasis

(14) ITALIANATE STYLE (1850-1880)

The Italianate style was introduced in America by English pattern books based on the latest fashion overseas. England was influenced by the informal design of Italian style as part of the Picturesque movement. This movement deviated from the formal classical design in search of a style freer in its expression. In America, the style was adapted and embellished, making it unique to the country. American pattern books by Andrew Jackson Downing defined and promoted the Italianate style in America.

Italianate buildings usually are two or three stories and are rarely found in one story. The roof is low-pitched with wide overhanging eaves supported by decorative brackets. Windows are generally one or two pane sashes that are tall and narrow, with arched or curved upper sash. The windows are often decorated with ornate hoods, typically an inverted U- shape. Porches are very common in the Italianate style with smaller entry porches being most common.

Full width or wrap around porches are usually found on larger buildings or on those buildings that are "high style." Front doors can be found in the same shape as the windows with large pane glazing.

(15) IDENTIFYING FEATURES

Wide, overhanging eaves

Two or three stories

Single or paired brackets

Embellished Cornice band

One or two pane windows

Paired doors

Elaborate ornament

Tall, narrow windows

Arched ornate windows

One story porches

(16) SECOND EMPIRE STYLE (1855-1885)

The Second Empire style is named after Napoleon III's reign over France (1852-1870). During his reign, advancements in design and fashion made Paris the world's center for art and architecture. The Second Empire style was considered to be a modern design and reached America by way of England. The most notable defining feature of this style, the mansard roof, was named after the architect Francois Mansart because of his widespread use of this roof type in his designs. This style also was popular for remodeling buildings because the mansard roof provided a full-story attic space (which was not historically taxed as usable space).

The Second Empire mansard roof generally comes in five shapes: straight, straight with flare, concave, convex and s-curve. It is common to find decorative patterns of color or texture on the roof with an iron crested cornice widows walk. Underneath the roof-line the Second Empire is closely related to Italianate style but the eave overhang is not as large and there is normally an arch above the windows.

(17) IDENTIFYING FEATURES

Mansard roof

Dormer windows

Molded cornices

Decorative brackets

Cast iron cresting at rooftop

Brackets below eaves

Cupola covered by roof

Patterned roof slate

Two (2) or three (3) clusters of windows

Projecting central bay

Quoins (corner details)

Many textures and colors

(18) EASTLAKE STYLE (1880-1890)

The Eastlake style is named after Charles Eastlake, an English architect who influenced building design through the publication of his book Hints on Household Taste (published in 1868). This look deviates from the curvilinear earlier styles in favor of angular, notched, and carved elements influenced by Medieval designs. Incised patterns were commonly found on hood moulds and brackets. Three-dimensional ornamentation became popular to this style because of the new advances in technology for woodworking machinery, such as scroll saws, chisels, power lathes, and spindle shapers. The power lathes and spindle shapers are the two tools that made the fancy details and posts. Eastlake style ornamentation was commonly applied to other Victorian buildings, primarily designed in the Queen Anne and Stick styles.

(19) IDENTIFYING FEATURES

Large, scrolled brackets

Floral ornamentation

Geometric ornamentation

Incised decoration

Oversized elements

Angular, notched elements

Asymmetrical design

Many textures and colors

(20) ROMANESQUE REVIVAL STYLE (1880-1900)

Architect Henry Hobson Richardson designed in the fashionable styles of the second half of the 19th century, including Second Empire, Queen Anne, and Stick. He later adapted these styles creating a new style that became known as Richardsonian Romanesque. This style creates the appearance of a massive and solid structure, causing it to become popular for large public buildings of that time.

The common Romanesque Revival form is a hipped roof with a cross gable, but was also built-in town house form. The buildings are often constructed out of rough-faced stonework with two or more colors creating decorative wall patterns. Wide-rounded arches are a distinct feature above windows, entryway or porches. The arches are supported by massive piers or are built into the wall. The Romanesque Revival was less common in residential design in Ohio because its solid masonry construction was expensive.

(21) IDENTIFYING FEATURES

Round-topped openings

Arches rest on columns

Deeply recessed windows

Grouped windows

Round tower

Asymmetrical facade

Rough-faced masonry walls

Two or more colors

Many textures of stone

(22) QUEEN ANNE STYLE (1880-1905)

The Queen Anne style originated in England with a group of architects under the leadership of Richard Norman Shaw, who also introduced the style in America during the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition of 1876. Pattern books detailing the design encouraged the advancement of this style across America. Popularity of the Queen Anne style grew because the defining decorative elements could be pre-cut and transported by railroad. A boom in the economy during the time this style was popular resulted in many structures being built in the Queen Anne style.

The Queen Anne roof is irregular in shape and is steeply pitched with a dominant front-facing gable. Methods are used to avoid a smooth-walled appearance such as patterned shingles and cutaway bay windows. The building is normally asymmetrical with a one-story high partial or full-width porch.

Four decorative detailing types are common on a Queen Anne style building: spindle work, free classic, half-timbered and patterned masonry. Spindle work is present on the porch balustrades and suspended from the porch ceiling creating a frieze. Free classical columns are on the porches usually full height or on a raised pedestal. The supports are often grouped together in three but lack the decorative detailing.

The porch is supported with solid spandrels and often has half-timbering or decorative timbering details on the front gables or upper stories.

(23) ITALIAN RENAISSANCE STYLE (1890-1935)

By the late 19th century many American Architects and their clients had visited Italy to see and experience the style first hand. Technology was improving and so was the quality of printing. The use of photographs to document the buildings became popular. The earlier Italianate style was based on pattern book drawings by professionals with no firsthand knowledge of Italian buildings. After World War I, masonry veneering was perfected which allowed buildings to closely imitate the stucco or masonry walls of the original Italian models.

Italian Renaissance structures are symmetrical in form and typically found with low pitched roofs that are covered in ceramic tile including broadly overhanging boxed eaves with decorative brackets below the eaves. All openings have arches above them and the upper windows are less elaborate than the first floor full-height windows. The entrances are recessed and supported with small classical columns or pilasters.

(24) IDENTIFYING FEATURES

Low-Pitch Roof

Arches Above Openings

Symmetrical

Ceramic Tile Roof

(25) NEOCLASSICAL STYLE (1895-1950)

Neoclassical style sparked interest after the World's Colombian Exposition in 1893 and the 1901 Pan-American Exhibition in San Francisco.

Famous architects of that time showcased their dramatic designs of white colonnaded buildings. The buildings of the Exposition were monumental and inspired many commercial and public buildings thereafter. In the first half of the 20th century Neoclassical became a popular style for domestic buildings throughout the country. The first wave of these buildings occurred from 1900-1920 and displayed hipped roofs, elaborate classic columns, and pedimental entries. The second phase occurred from 1925-1950, which included side-gabled roofs and simple columns.

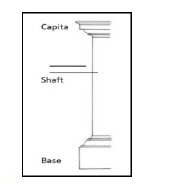

Neoclassical houses normally have a boxed eave with a moderate overhang and employ full-height porches that are supported with classical columns, with Ionic or Corinthian capitals. The facade is symmetrical with a central door and balanced windows. The door is elaborately decorated and the windows are double-hung and rectangular.

(26) IDENTIFYING FEATURES

Dominate front porch

Roof supported by columns

Ionic or Corinthian capitals

Symmetrical windows

Center door

Elaborate doors

Boxed eave

Moderate overhang

Rectangular windows

Pediments

(27) CRAFTSMAN STYLE (1900-1925)

The Craftsman style was part of an international movement of style, art, and philosophy with William Morris, a 19th century English designer, being a large part of the movement. The Craftsman style in the United States was inspired by two California brothers: Charles Sumner Greene and Henry Mather Greene. Their designs were influenced by the English Arts and Crafts movement, and Oriental wood architecture. The designs focused on the natural beauty of the materials, and detailed craftsmanship with simple clean lines. Ornamentation was kept to a minimum. Publications of Green & Green's designs in magazines such as the Ladies Home Journal and Good Housekeeping helped to popularize the style. Furniture manufacturer Gustav Stickley published a popular magazine called The Craftsman, featuring both architectural and furniture designs.

The style became so prevalent that a flood of pattern books was produced. Some companies, such as Sears, offered entire packages of pre-cut lumber, doors, windows, plaster, trim, and fixtures.

The Craftsman style porch is supported by columns that are short and square and sit upon simple pedestals; these pedestals, columns, and piers frequently extend to the ground. The most familiar characteristic is the roof overhang. The roof rafters are usually exposed and sometimes have decorative details. The doors and windows are similar to Prairie style homes. The dormers have gables with exposed rafters at the end. The most common wall-cladding is wood clapboard and wood-shingles. However, stone, brick, concrete block, and stucco variations can be found in northern or mid-western states.

(28) IDENTIFYING FEATURES

Low pitched wide gable

Unenclosed eave

Rafters exposed

Full or partial-width porches

Tapered square columns

Columns extend to ground

Beamed ceilings

Casement windows

(29) TUDOR REVIVAL STYLE (1910-1940)

The Tudor Revival style is modeled after a variety of late Medieval English styles; the prototypes range from thatch-roofed folk cottages to grand manor houses. The traditions are openly mixed in their American Eclectic representation but are unified by distinctive characteristics such as steeply pitched roofs, front-facing gables and a prominent entry facade. Nationally, the style saw its height of popularity beginning at the end of World War I and continuing through the 1930s.

The buildings frequently have steeply-pitched roofs with the facade dominated by one or more prominent cross gables. The windows are tall and narrow with multi-pane leaded glazing (diamond patterns are very common). The chimneys are massive and are usually crowned by decorative chimney pots.

(30) IDENTIFYING FEATURES

Steeply pitched roof

Stone, brick or stucco

One or more cross gables

Decorative half-timbering

Tall, narrow windows

Massive chimneys

Decorative chimney pots

Gables overhang

Asymmetrical plan

Round or Tudor arch entry

Leaded glass windows

(31) ART DECO STYLE (1925-1940)

Art Deco style grew during the time period between the two World Wars. The Exposition des Arts Decoratifs, an exhibition held in Paris in 1925, was part of an International Style movement. It was inspired by Cubism, Futurism and Constructivism; America's obsession with the future, speed, and transportation (such as the car and train) was also a driving force behind this movement. The style was honest and simple, but most of all it was functional. The structures combined rectilinear massing, futuristic images, stylized ornament and polychromatic effects. This glamorous style changed the shape of virtually everything in America, from the American home to jewelry and other decorative arts Deco with some Gothic details.

(32) IDENTIFYING FEATURES

Smooth and flat wall

Geometric designs

Vertical emphasis

Inspired by machines

Inspired by movement

Horizontal band of windows

Curved window glass

1/1 windows

Metal doors

Metal window sash

(33) APPLICATION REVIEW AND PROCEDURES

The process to review proposed work within the Design Overlay District (presented herein) is defined in Section 1104.01

of the Kent Zoning Code.

(34) ARCHITECTURAL REVIEW BOARD

Work that will affect the exterior of a building in the applicable overlay districts will be required to obtain a Certificate of Appropriateness issued by the Architectural Review Board of the City of Kent. The Certificate of Appropriateness when mandatory must be issued for a project prior to the issuance of a Building Permit.

(35) USE OF THE GUIDELINES

These Design Guidelines must be used in conjunction with new construction and existing building alterations, signage and as otherwise applicable with the applicable Design Overlay District(s) and for the use of the Architectural Review Board when reviewing projects subject to these Guidelines. These Guidelines are based upon the Secretary of the Interior Standards for Rehabilitation (see Appendix B), explain how to look at an historic structure or structures within the district, and how to evaluate its characteristic for preservation, rehabilitation or suitable new additions within the overlay district(s). These standards are used for new construction to ensure that it is compatible with the existing nearby structures and amenities. Those individuals using the Guidelines either voluntarily, in conjunction with a City assisted project, or who are using them in conjunction with a mandatory review within one or more of the Design Overlay District(s) in the City are encouraged to read these guidelines in their entirety. Those sections noted in bold print are especially important and are prescriptive in nature. These prescriptive elements identify the key points to be considered by the Architectural Review Board in their review of an application for a Certificate of Appropriateness.

(36) FINANCIAL INCENTIVES

The City of Kent has chosen to mandate the use of the Guidelines and the review process for projects that are funded, in whole or in part, by the City of Kent If a property owner chooses to take advantage of the federal or state historic preservation tax credits, that owner must follow the Standards for Rehabilitation (Appendix B); which are the principles upon which the Kent Guidelines are based.

WHAT DOES ADOPTION OF THE KENT DESIGN GUIDELINES MEAN?

Adoption of these Design Guidelines means that the citizens of Kent wish to be proactive in the success of their community, acknowledging Kent's special heritage and its unique and eclectic architectural personality. The Guidelines are a tool for the community, especially within the recommended Design Overlay District and any future designated area, to protect and support the character that brings such pride.

The Guidelines are a tool to assist the public and to assist the Architectural Review Board so as to support consistent recommendations. In the end, the goal declared by the community throughout this process is: Perpetuate good design to help economic vitality and sustain property values.

(37) PRESERVATION PHILOSOPHY

The preservation philosophy that these Design Guidelines aim to uphold is based on the Secretary of the Interior's Standards for Rehabilitation. The philosophy's purpose is to retain original or historic building materials to the greatest extent possible and to avoid creating a false historic appearance when elements must be replaced. Replacement materials should match the originals in size, color, and texture. Substitute materials such as vinyl for wood should be avoided. New additions and new construction may be distinguishable from the historic while being compatible with the existing structure or surrounding structures. Additions and new construction should be reversible, so if removed, it will not impair the historic structure's form or integrity.

(38) PRESERVATION PRINCIPLES

Refer to the Secretary of the Interior's Standards for Rehabilitation located in Appendix B.

(39) DESIGN PRINCIPLES BUILDING TYPOLOGY

In addition to understanding building styles, it is important to understand general building types. Building type or typology is the form a building takes related to its materials, function, and visual organization. It also can describe a regional or vernacular method of building, related to form rather than style and ornament. It is important to be able to describe, critique, and prioritize these components of architecture. Successful design within an existing historic context includes both an understanding of the typology of the existing structures, as well as the meaning of their style in a place in time.

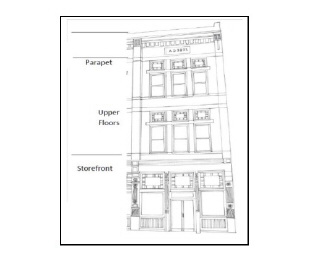

(40) FABRIC AND OBJECT BUILDINGS

Within the context of the Kent Design Overlay District, there are two principal building categories: Fabric Buildings and Object Buildings. Fabric Buildings make up the sense of place and they define general character and set scale. Fabric Buildings typically have a commercial or residential use. They are the majority of the buildings and are usually built during the same time period. They are principally a commercial block type with a basic three-part form: a glass storefront base, upper floors with "punched" window openings, and some form of cornice. The majority have a flat roof.

Object Buildings are buildings of cultural or civic importance and have a symbolic presence to Kent. Object Buildings can include churches, post offices, theaters, libraries, town halls, courthouses, and other civic or cultural institutions. These buildings have a variety of forms and visual organization and are not necessarily part of the town's standard fabric.

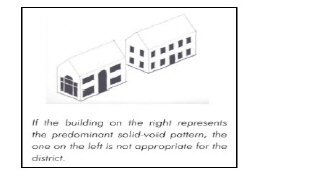

When considering the application of design principles to new work in an existing context, the priority of the design principles ranges from the general to the specific. A well designed building placed poorly on the site undermines the overall design. A poorly proportioned building with elaborate details will fail to fit within an existing context because the observer sees the form first and the details second. Conversely, a building placed and proportioned appropriately with simplified or contemporary details will work well within an existing context. Therefore, the priority of the design elements should be as follows.

Building Placement

Form

Solid/Void Pattern

Facade Organization

Materials/Color/Texture

Details

(41) BUILDING PLACEMENT

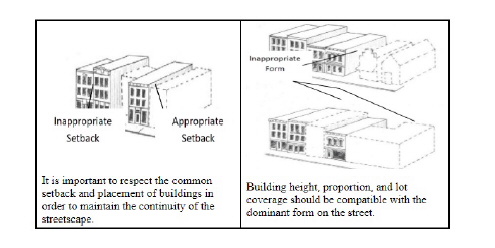

Within an existing context of historic buildings, there is a customary or prescribed building placement. It is important to respect the common setback and placement of buildings in order to maintain the continuity of the streetscape.

This should be regarded as a "build to" line, as well as a building setback.

Consideration should also be given to the vistas both along the streetscape or roadway for structures set near the road, and from the road for structures set back away from the road. Carefully consider any new construction adjacent to the existing structures: will the new construction interfere with the views?

(42) FORM

Whenever possible, the existing historic context of the building form should be respected, including the volume of the form in relation to its site. Building height, proportion, and lot coverage should be compatible with the dominant form on the street. Orientation of the form to the street also should be the same as the context. For example, if all of the buildings on a given street are gable-fronted facing the street, new infill buildings should have a similar form and orientation.

(43) SOLID/VOID PATTERN

The ratio and pattern of wall-to-window openings is common within a given building type and age. Respecting this pattern helps to unify the streetscape.

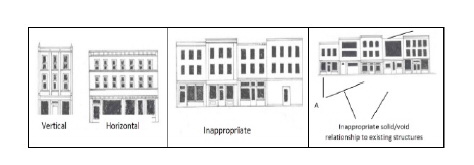

(44) FACADE ORGANIZATION

Horizontal versus vertical facade organization of architectural elements is usually similar within a given context. Some buildings have prominent horizontal elements such as belt courses, continuous sills or lintels, or projecting cornices or entablatures. Other buildings exhibit an emphasis of vertical elements such as continuous pilasters that separate the facade into spandrel panels.

When a dominant pattern of either horizontal or vertical organization exists in the historic context, this pattern should be imitated by any new construction.

(45) MATERIALS/COLOR/TEXTURE

Selecting materials that are compatible in color and texture with adjacent structures helps to create a unified design within the district.

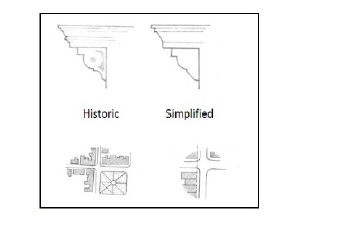

(46) DETAILS

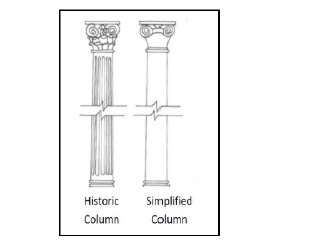

Imitating details of historic structures exactly when creating new structures is generally not necessary or desirable. Respecting the general placement, form, visual organization, colors, and materials within a given context is sufficient to create a new building that is compatible. It is not necessary to create a replica of an historic building by copying exact details. Simplified details of similar proportions to those found within the district are sufficient.

(47) GENERAL RECOMMENDATIONS

(48) IN CARING FOR KENT HISTORIC STRUCTURES

• Inspect and maintain building elements on a regular basis.

• Repair before replacing elements or materials. Replacement is an option only after all other possibilities have been considered.

• Avoid adding elements to a building that were not originally present.

(49) MISSING ELEMENTS

• Replace or reconstruct the missing element using materials that match the original as closely as possible.

• If no evidence can be found to document the element's original appearance, replacement should be consistent with the building's size, scale, and materials. The replacement should be simplified to avoid creating a detail that may not have been part of the original design.

• Examining other buildings of the same architectural style can help determine what may be appropriate.

(50) DETERIORATED ELEMENTS

• Avoid giving a false impression of historic character by use of ornament not appropriate to the time period and stylistic influences. Repair deteriorated elements as soon as possible to prevent further damage or loss of material. If an historic element is deteriorated beyond repair and removal has been approved, document with photographs and measurements before removal. Then reproduce the element, matching the original design and materials.

(51) NON-ORIGINAL ELEMENT

• If an element has been previously replaced, consider retaining the existing element if it is unique, aesthetically complements the building, or is a good example of what was in style in its own time (i.e., a well-designed and constructed 1880's porch on an 1840's house).

• If the element is considered inappropriate for the building, replace the element with one that is appropriate.

(52) SALVAGE MATERIAL

• Avoid adding elements to a building from other structures. This generally creates a false history and would be inappropriate. Respect each building for its own design and style. If salvage material is used for repairs, such as old brick that matches the correct size and color, it is appropriate to mark the salvage items on the back so that they can be identified later.

(53) STOREFRONT

The main purpose of storefronts and their windows is to display items for sale in a store. They are, however, a very important part of the pedestrian experience, influencing the public perspective of the district.

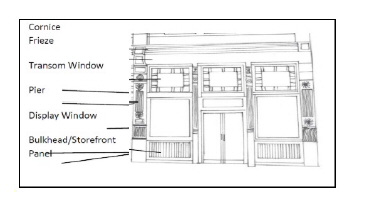

Traditional storefronts were regularly designed in a three-part composition: a fairly low bulkhead at the base, large glass display windows, and transom windows at the top providing additional natural light to the interior. Transom windows often had small panes of prism glass that gathered light and projected it toward the rear of the stores.

Surviving historic storefront elements (such as bulkheads, wood or metal trim or window hardware, and transom windows) should be retained if at all possible. Such elements are part of the fabric of historic Kent and contribute to its character and high visual quality. Designs for new storefronts or renovations to existing ones should be respectful of the size and proportions of elements typical of the area's older storefronts. They should, for example, have bulkheads, display windows, and transoms. The storefront must fit within the original storefront opening that is defined by end piers or columns and horizontal members. Piers and columns should remain exposed.

Refrain from making the storefront look like a residence or office through the use of small or multi-paned windows. If necessary, screen large display windows with interior blinds if privacy is desired for an office use.

Traditional materials should be used when storefronts are rehabilitated or reconstructed in older buildings. Bulkheads should be paneled wood for 19th and early 20th century buildings, though ceramic tile was sometimes used, especially in the 1920s. Brick and stucco were not typically seen in the bulkhead area. Display windows usually were supported by fairly light wood or metal framing systems, leaving a maximum glass area. Heavy wood framing or masonry materials were not typically used in the display. Transom windows were commonly framed in wood or metal. The glass was usually clear, to transmit maximum natural light into the store.

(54) DOORS

Entrances of historic buildings have always been one of the main elements that help define the overall style and design of a structure. Typically, the door is the main focus of the entrance.

It is because of this that many historic doors have been decorated and embellished with moldings and other decorative panels and motifs found throughout the structure. In maintaining the general style and importance of an historic structure, it is essential to preserve the value and significance of an historic entrance door.

Historic entrance doors should be preserved and maintained whenever possible. They should be kept in operable condition, allowing for smooth opening and closing. Doors performing poorly should be re-hung before shaving or undercutting. Their hardware and thresholds should be tightened and maintained. Historic doors that do not match the time period of the structure should still be preserved as existing historic doors are more valuable and accurate than any new door designed to match the building.

Only deteriorated or missing portions of an historic entrance door should be replaced. These replaced elements should be reproduced to match the original material and style. If replacement of the entire door is necessary, the original frame should be preserved, maintaining the dimensions and location of the door. Historic hardware and glazing should be salvaged and preserved. It is preferred that the replacement door be a replica of the historic door. If this is not possible the new door should match the style of the historic structure.

A new entrance door to an historic building should be contemporary in design but compatible in size, scale, material and color with the style of the building. Restoration of a missing historic door is appropriate only with historical, pictorial or physical documentation.

Because doors are such a prominent feature in a building, it is essential that the door, restored or reconstructed, hold the style of the structure without altering its character. For example, a residential type door should not be placed on a commercial building.

(55) AWNINGS, CANOPIES, CORNICES & PARAPETS

A. AWNINGS AND CANOPIES

These features are used to shade window openings to keep down the interior heat in the summer, awnings typically made of canvas or similar heavy fabric are mounted on solid metal or pipe frames. Awnings provided protection both from the sun and from inclement weather, and they can often be rolled or retracted to allow the sun into the building during cool weather.

With the current interest in "green" practices, awnings are a highly efficient passive device considered to be a worthwhile investment not just for appearances. Fabric awnings are an appropriate treatment for most residences in the historic districts and for many commercial structures. Avoid fixed, permanent canopies unless it can be shown through research that a building had them in the past and that the canopy design is compatible with the original character of the building and the specific district.

Each window or door should have its own awning, rather than a single full-width awning covering multiple openings or an entire facade. Use a traditional flat, sloping awning. Awnings should have a matte rather than a glossy surface. Avoid rounded or "bullnose" awnings, except at round headed window openings where the rounded awning shape is appropriate.

Awning color is important. Manufacturers can provide durable, long-lasting fabric for awnings in a wide range of colors. Awning colors should be compatible with historically appropriate colors used on the building, avoiding ornate patterns or too many colors.

B. CORNICES AND PARAPETS

The cornice is a projecting horizontal band at the top of the facade. Commercial structures often have an additional cornice located at the top of the storefront.

The parapet is a low wall that extends along the roof edge. This wall often has decorative detailing and is frequently combined with the cornice to produce a cohesive crown on the building's facade.

The combined elements are typically a more elaborate design of the cornice and frieze located at the top of the storefront. Ornamentation, including the style of trim and use of brackets to support the cornice, is distinct to a specific architectural style.

Address cornice and parapet repair immediately. If repairs must be delayed, take measures to keep the public safe from debris that may fall from above. The cornice and parapet should not be covered with non-original or incompatible materials, unless it can be demonstrated there are no other reasonable alternatives. Waterproofing treatments can prevent the parapets from properly drying after a rain or snow fall, thereby causing more damage; this type of treatment should be avoided.

C. UPPER FLOORS

The upper floors of the 19th and early 20th century commercial buildings in Kent are designed with a rhythmic pattern of windows and may utilize projections such as towers, oriels, or balconies to create a more three-dimensional appearance.

Windows on the facade of the upper floors are often embellished with ornament that is characteristic of the building's architectural style.

The size, spacing, and proportions of the windows are determined by the overall composition of the building and its storefront. These windows were typically double-hung and contain clear glass panes. The number of window panes relates to the style of the building. Upper-floor windows usually have one-over-one double-hung sash by the end of the 19th century. A few buildings have windows with metal sash, revealing a narrow profile.

The most economical and historically appropriate method for revitalizing windows is to repair the original ones. New windows are generally heavier, with bulkier sash and muntins, and do not retain the appearance of the original windows. The older glass also has characteristic imperfections that new glass will not have.

When windows need to be altered or replaced (in-filled, downsized, or replaced with contemporary windows), original window openings should be maintained at their original size. It may be appropriate to use new replacement windows with the same profile as the originals. Occasionally it is necessary to replace severely deteriorated windows. If approved, new windows need to match the profile, design, material, size, and construction of the original. To discourage vandalism and avoid an abandoned appearance, interior window treatments may be added to unoccupied floors.

Exterior storm windows are recommended to increase energy efficiency and help preserve the historic windows. Storm sash should complement the dimensions of the historic windows. Interior storms may be preferred in limited circumstances involving highly ornate windows. They must be ventilated to avoid condensation build-up on the historic sash and trim. Other windows accessories, such as added shutters or added ornament, are inappropriate without evidence that they were originally present.

Other architectural features that may appear on Kent's historic buildings are balconies, oriels, and projections. Often these types of features were used to give dimension to the upper parts of taller buildings.

Intact architectural projections should remain and be maintained. Reproduction of missing features should be considered when historic documentation presents evidence of the elements' prior existence. Consider uncovering these elements if a contemporary facade hides them from view.

(56) PORCHES

Porches are key elements that help define the character of both the building and the streetscape. Porches are the architectural transition between the public street and the building interior.

It is important to maintain the original porch structure and porch elements, including railings, posts, steps, and ornament. If one of those elements needs to be replaced, duplicate it using the same material and design.

Enclosing a porch is an extreme change to a significant feature and should be avoided. If constructing a new porch to replace a missing porch, model the design on archival or physical evidence to the greatest extent possible. If neither exists, refer to examples of historic porches on comparable structures and keep the design simple.

(57) FOUNDATIONS

Building foundations in the Kent Design Overlay District range from rubble stone (pieces of stone simply picked up and carried to the building site) to cut stone, which was worked by hand, to brick or more modern materials such as rock-faced concrete block and poured concrete.

The purpose of each foundation is the same: the foundation carries the weight of the building down into the soil, spreading the weight so as not to exceed the bearing capacity of the soil.

On some buildings, the foundations rise only slightly above ground level and often are nearly invisible. On others, higher foundations became part of the building's visual character. Many of the Kent's foundations have extra detailing such as chiseled margins, peaned surfaces, or other markings from the quarrying process.

Improper maintenance or alterations to foundations can adversely affect their capacity to function properly. The building can 'settle' resulting in cracked plaster, damaged masonry, and uneven floors. It should be noted that buildings can settle immediately after their construction, causing the same effects along with windows and doors out of plumb. If the initial settlement has ceased, the problems may be minor; continuing settlement is a problem for which to seek professional help.

To prolong the life and reduce necessary maintenance on the foundation, there are a few things that can be accomplished. Soil, paving materials, and plantings beds must slope away from the foundation to provide positive drainage. Check gutters and downspouts or internal drainage systems to be sure that they are operating properly. If gutters are sloped improperly, water will spill down the side of the building. Be sure that downspouts are connected into underground drains or empty onto splash blocks or extensions of pipe that carry the water away from the building's base. Be sure, also, that the downspouts do not empty onto pedestrian paths.

Foundations like to breathe. The easiest way to do that is to allow eighteen (18) to twenty-four (24) inches clear space from the foundation to any planting. Vines and other plants should not be allowed to grow on the foundation. If vines are a desired feature, they should be cut all the way back to the base periodically. They will grow faster and softer if they are "clear cut." Dirt, mulch, and firewood should be piled away from the foundation as they hold the dampness and often hold termites (yes, termites will go through the masonry foundation!)

Most foundations are ventilated. If there are vents in the walls, it is important to keep the air flowing through them; consider adding ventilation if there is none. If security is an issue, consider adding a simple iron grate in front of the opening.

Avoid cutting new openings in foundation walls. If you do such alterations, do it with the advice of an architect or structural engineer to avoid the possibility of weakening the foundation.

(58) EXTERIOR WALLS

Exterior wall materials vary throughout Kent, ranging from brick and stone to several types of wood siding; Kent's buildings are a menagerie of architectural styles.

The general approach to the exterior walls of historic structures is to maintain the original materials: their lifespan increases with proper care. Brick walls need to be kept clean of salt from sidewalks in the winter and vines from the summer gardens. Occasionally, the owner may find the need to repoint the mortar joints. It is essential, to clean using the gentlest means possible. High-pressure water methods can drive water into the walls, causing problems on the inside of the building, and erosion and damage to the exterior.

Whether the walls are brick or wood, the original material should not be covered. The act of covering can be detrimental to the original materials and detracts from the original design, altering the original details and the original colors and textures of the building. If the building has already been covered with a subsequent siding, consider removing it. Substitute materials such as vinyl or aluminum are not appropriate for use in the Kent Design Overlay District. Even on new construction within an historic district, vinyl and aluminum siding may not be appropriate. Refer to the National Park Service Preservation Briefs on Subsistent Materials for further information.

Repair of existing siding is the best option. For repair of severely deteriorated wood siding in the Kent Design Overlay District, new siding should be designed, purchased or milled to duplicate the appearance of the original siding, matching its width, profile, and material. Siding will remain in good condition if the owner ensures the integrity of the finishes on the siding. If the original material was painted, it is necessary to maintain a good painted finish.

(59) ROOFS, GUTTERS, CHIMNEYS, SKYLIGHTS AND DORMERS

Together the roof, gutter, and downspout provide a path for collected water to be removed before it can enter the building. Moisture is a primary cause of damage to building materials and historic elements.

Removing water before it infiltrates the building or the finishes can prevent a multitude of problems and is much easier to do than trying to remove water once it is inside.

The roof of a multi-story commercial structure in Kent is typically flat and sloped only slightly towards the back of the building to assist with water drainage. The roofs on residential or adaptive use residential (now commercial) are most likely sloped and in a variety of configurations. The guidelines are the same, however. If the roof is flat, it is appropriate to use modern materials when the roof is reapplied. Some items to watch for would include proper repair of the parapets and proper detailing for the materials that are applied to the flat roof. Maintain proper drainage from any roof.

On roofs where the materials are seen from the ground or from adjacent buildings, the original material is the ideal roof covering. If the original roof can be repaired, that would be the recommended course of action. Slate, wood, or tile shingles add character to the original design. The original materials, however, have often been replaced. In this case, it is ideal to restore with characteristic historical materials, but using a more economical shingle may be a reasonable approach (an acceptable replacement material).

Changing the configuration of the roof, no matter how slightly, can alter the appearance of a building drastically. Historic ridge caps, weather vanes, dormers and chimneys should be repaired and maintained. Chimneys can sometimes be used for mechanical chases, or capped, but their appearance on the roof is extremely important to the character of the historic building. Ensure also that gutters and downspouts are operational to increase the longevity of the roof and building system.

New skylights (passive solar energy) should be flat to the roof and may be considered on an historic building if they cannot be seen from the public view.

Skylights were used historically as well. Properly restoring an existing skylight is appropriate and encouraged. Often historic skylights were covered to prevent leaking. With new technology, there are some appropriate methods to upgrade historic skylights to prevent leaking and energy loss.

Roof top equipment of any type is detrimental to the appearance of buildings and may be used only if the elements are not visible from the streetscape.

(60) OUTBUILDINGS

The description of "outbuildings" includes the garages, sheds, barns, and carriage houses often associated with older residential buildings. Sometimes, these buildings reflect the architectural design of the house with which they are associated. Often these structures are simple, utilitarian design.

Because outbuildings contribute to the area's overall character, property owners should give due consideration to their care and construction. Original outbuildings such as garages, carriage houses, sheds, and barns should be left in place and repaired as necessary. These structures add variety and character and their removal should be avoided. When outbuildings need repair or when deteriorated elements must be replaced, use new materials that match the old as closely as possible. Avoid modern materials that are incompatible with original designs of these structures. Newly-constructed outbuildings should take design cues from the older nearby structures. The design should use forms, massing, roof shape, materials, window and door types, and detailing similar to those found on the main structure or other nearby outbuildings. The goal should be to create a new building compatible in appearance with those already in the neighborhood.

(61) SIGNAGE

Signs are often controversial; perhaps it is because the contents are so personal. The sign is the face the business displays to the public with importance similar to that of the building's façade. Occasionally, a sign is deemed by popular opinion to be offensive. Ideally, popular opinion is not the most positive approach, nor the most direct approach, to good design.

In an effort to quell the controversy over signage, many cities and towns have zoning ordinances to standardize sign size, placement, content, construction, and illumination.

Kent's sign requirements are currently included in the Planning and Zoning Sections of the Codified Ordinances and can be enforced in a manner similar to any other zoning violation. Future coordination with the current sign regulations and these Design Guidelines should be a goal for the city.

The Zoning requirements for signage must supersede these Design Guidelines, however, upon recommendation by the Architectural Review Board, the City's Board of Zoning Appeals may consider the granting of a zoning variance for a sign within the Design Overlay District.

Sometimes overlooked, the sign is a powerful tool for advertising and business purposes; however, equally powerful is the image that the sign conveys about a particular business and the commercial district as a whole. The style and design of signage has evolved over time, but its purpose has always been the same: to demonstrate to potential customers and clients the purpose of a business and how to find it.

Early 19th century signs were often painted directly on the building or were painted on wooden signboards that could be attached to the building. Care and maintenance of these traditionally painted building signs should be encouraged. Signs could be mounted flush on the building wall, but could also be suspended out over the sidewalk perpendicular to the building. Historically, these suspended signs were often supported by ornamental wooden brackets. By the late 19th century, there was a greater variety of signage types and designs. Signs were incorporated as part of the storefront design, some used leaded or stained glass, and some were painted on the inside of display windows. Historic commercial buildings often provide clues to the form and location of an appropriate sign.

During the late 19th century and the early 20th century signs were frequently integrated into the design of the storefronts and buildings. Space above the storefront was often reserved for a sign board or for a projecting sign hanging perpendicular to the storefront. Display windows sometimes held painted window signs.

Fabric awnings also provided location for signage. Signs such as these might contain letters (painted or applied individual letters) or symbols which gave a quick graphic reference to the business inside. These signs reflected appropriate treatments for a commercial district sign by use of quality materials and design, pedestrian scale, proportional size, and appropriate location.

New signage should be designed and constructed using materials and methods that are consistent with the building's architectural style. The size should be limited to the smallest size necessary to reach the public. The Kent Zoning Code defines requirements for the maximum size, number and placement of signs.

Size should relate to the location for which it will be placed on the building. Color and lettering of the sign should complement the architectural character of the building. When attaching the signs, one should be conscious not to damage historic materials. Small signs can be placed at secondary entrances that are accessible to the public in order to identify the business and should also comply with the above recommendations, if permitted by the Kent Zoning Code. Signs that address the second floor may also be allowed if permitted by the Kent Zoning Code.

In an effort to attract attention, signage is sometimes inappropriately designed, sized, and placed on buildings, resulting in a negative effect upon both the business and the entire area. Business owners should remember that treating the signs as an integral part of commercial architecture can have a positive impact on the appearance of the buildings and the historic districts.

The impact signs may have on the district and especially the adjacent structures are important but is often difficult to measure. If the signs are poorly maintained, clearly that can have a negative effect. The current zoning code has maintenance provisions. These guidelines suggest a reasonable approach to the design of the sign, just as one would approach the design of the building.

The use of neon must be regulated by the sign regulations in the Kent Zoning Code. If permitted, such neon signage must not be allowed to flash or appear to move. The guidelines suggest that the signs be stylistically appropriate to the building and to the district. If the building is a 1950s stainless steel diner, neon may be appropriate. If the building is a 1940s theater, a large marquee with flashing lights may be appropriate.

Neither neon nor flashing signage types are appropriate for a converted Italianate home that now serves as offices.

It should be noted that other considerations in the design of the signage would include light pollution and unnecessary use of energy. In a pedestrian friendly downtown district, one may suggest that signs of a more modest scale be recommended rather than those required to be read from the highway. It is necessary to refer to the Zoning Code for the City of Kent along with the Guidelines to be sure that the signage and lighting are appropriately designed.

(62) EXTERIOR LIGHTING

Exterior lighting is a necessary feature of an architectural environment. It is generally used for safety and aesthetic purposes. Lighting allows pedestrians to see where they are going, illuminating a pathway or obstacle in front of them. It instills a sense of security in people while in public spaces. Proper lighting can also provide charm and visual identity to an historic building. Brightening an inviting entry or casting light on an important architectural feature could enhance the character of an historical structure.

Existing historic light fixtures should be preserved and maintained whenever possible. Removing existing lighting could alter the character of a historic structure and is strongly discouraged. Exterior lighting should be used to illuminate entrances, walkways and significant architectural features. It should be appropriate and compatible with the style of the historic building. Lighting should be kept at low levels of intensity so that neighboring properties will not be affected by excess light. New lighting should be minimal; it is recommended that fixtures are simple, durable and discreet. Any new lighting installed on a structure should cause no damage to the building and should be fully reversible.

(63) HISTORIC INTERIORS

Building interiors are generally not "regulated" by City Ordinance. Guidelines are helpful to those building owners who may wish some assistance. For building owners who are taking advantage of The State or Federal Historic Preservation Tax Credit, the interiors are important because The Ohio Historic Preservation Office will request a description of the building's interior.

If a building has an interior with original features, it may be prudent to respect the existing material. It is recommended that owners of historic properties consider maintaining and retaining the interior features of their buildings. Interior features are equally important to understanding a building's historic, architectural, and cultural value.

It is important to research and identify key original elements of the building interior. If possible, retain original floor plans, particularly key circulation elements, such as interior hallways and stairways. Avoid subdividing large spaces unnecessarily joining smaller spaces. Always try to retain the original features such as interior trim, doors, interior hardware, mantels and cabinetry. Avoid "furring out" walls to install insulation or wiring which usually requires removal of the original trim. Installing dropped ceilings or covering original plaster walls with paneling should not be done. Removing plaster to expose brickwork or other masonry that would not have originally been left unfinished is not recommended. It is advisable to not paint millwork or woodwork that has not already been painted. Likewise, the recommendation for traditionally painted surfaces is for a similar finish.

COMMERCIAL USE OF RESIDENTIAL STRUCTURES

When re-using a house to serve a different function than its original purpose, the re-use should remain true to the building's original design and architectural style. Residences should not be significantly altered to accommodate a commercial purpose. If the basic layout and square footage of the structure is not sufficient, adaptive reuse for the particular function may not be appropriate. The size of the structure contributes to the scale of an historic district, therefore, caution should be used if it is necessary to enlarge a structure when adapted to a new use.

Do not alter the size, number, or style of window openings. Alterations to the entrance doors and door openings may be considered necessary to provide accessibility. Retain floor plans and elements of the historic interior that help define the character of the building; including size and configuration of rooms. Service areas and new stairs should be located in secondary spaces. Avoid altering spaces that are significant to the building's character, including subdividing spaces or cutting new holes in floors and ceilings. Avoid covering historic features, including the installation of drop ceilings that will cover ornamental ceilings or interfere with the tops of windows and window trim. Retain character-defining features and finishes such as columns, baseboards, fireplaces and mantels, and plaster. Avoid the removal, relocation, or alteration of historic stairs from their original configuration and location. New mechanical systems should be designed and installed in a way that will not harm character-defining spaces, features, or finishes.

Parking should be in proportion to the property and the building in both placement and scale. However, it should be carefully planned to direct patrons to the front door of the building, rather than a secondary entrance.

(64) ADDITIONS AND NEW CONSTRUCTION

A. ADDITIONS

Construction of an addition can often solve the need for more space. Because an addition can have a significant impact upon the character and appearance of an existing building, the design must be developed carefully. Owners should take into consideration issues of form, scale, proportion, materials, placement, and detail. The addition must meet the Kent Zoning Code, which is generally concerned with lot size, setbacks, placement, and parking.

For additions, material should be chosen for its compatibility with those of the original building. It is not necessary to use exactly the same materials (a frame addition is appropriate for a brick building, for example), but avoid materials that are not appropriate to the style and time period of the original structure. Scale, form, massing and quality are important even when discussing only materials.